GENERAL DOUGLAS MacARTHUR DUTY, HONOR,COUNTRY: The Enigma of American Leaders, there would not be a China problem today, the Vietnam War, and the Lies of Bataan The greatest enemy of truth is very often not the lie - deliberate, contrived and dishonest - but the myth - persistent, persuasive and unrealistic. --JFK, June 11, 1962 APRIL, 1942. ROOSEVELT SAID HELP WOULD BE ON THE WAY FOR BATAAN, BUT HE WAS LYING. HE CLAIMED THAT HE COULD NOT GET HELP THROUGH TO THE PHILLIPINES, HOWEVER IN APRIL OF '42 WE HAD THE BATTLESHIPS NEW MEXICO, MISSISSIPPI, IDAHO, COLORADO, MARYLAND AND PENNSYLVANIA IN SERVICE. THE BRAND NEW BATTLESHIP WASHINGTON WAS IN SERVICE ESCORTING SUPPLIES TO MURMANSK. WE COULD SUPPLY THE RUSSIANS BUT NOT OUR OWN TROOPS. THE AIRCRAFT CARRIERS LEXINGTON, SARATOGA, YORKTOWN, ENTERPRISE, HORNET WERE ALL AVAILABLE. THE WASP WAS BUSY ESCORTING SUPPLIES TO MALTA, ONCE AGAIN AT THE EXPENSE OF OUR OWN TROOPS! WHY DID ROOSEVELT DECIDE TO LET THOSE BRAVE SOLDIERS DIE WHILE HE HAD THE FORCE AVAILABLE TO HELP??? The flawed Europe First policy resulted in the death of American soldiers. These ships and troops should have first been allocated to protect American lives. To use our newest battleship to help Uncle Joe instead of making a task force to help Americans is criminal. People like to think Roosevelt had no choice but he did and he made a flawed political choice rather than a good moral choice. We could have taken the battle to the Japanese early on but the Pacific was always given a low priority in comparison with Europe. Since I don't recall Germany bombing us at Pearl Harbor the Europe first choice seems an odd idea that cost many Americans their lives. | p |

When retired General of the Army Douglas A. MacArthur made a farewell visit to his alma mater on May 12, 1962, it was to receive the Sylvanus Thayer Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the United States Military Academy. It was also an occasion for him to share his thoughts on the meaning of the West Point motto. “Duty, Honor, Country,” he solemnly intoned, invoking the three words that summed up the cadets’ calling. “Unhappily, I possess neither that eloquence of diction, that poetry of imagination, nor that brilliance of metaphor to tell you all that they mean.” It was perhaps the most eloquent downplaying of a speaker’s own rhetorical skills since Lincoln assured the gathering at Gettysburg, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” MacArthur proceeded to move both young cadets and battle-tested officers to the brink of tears with his eloquence of diction, poetry of imagination, and brilliance of metaphor. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the place,” said Bob Boehm, an airline pilot in New Hampshire who was a plebe at West Point at the time. “He was an amazing wordsmith and what an orator! He had an ability to say things so you could visualize exactly what he was talking about.” And hear it. And feel it. “When he talked about the sounds of the battlefield, you could almost feel the vibrations of the rounds going off, the explosions, even the smell of the battlefield,” Boehm recalls.  MacArthur was 82 when he made that final appearance at West Point, no longer as agile physically, perhaps, as he was when, as a spry 70-year-old, he ruled as viceroy in Japan, while simultaneously directing a war against communist forces in Korea. Yet his mind and his eloquent tongue roamed nimbly over his 50 years in the Army and more. His life covered an amazing span. “During his infancy,” wrote historian and biographer William Manchester, “Indians attacked his father’s troops with bows and arrows; in his later years — when he proposed that wars be outlawed — superpowers were brandishing nuclear weapons.” He grew up in an age when an automobile was still a rare luxury. He died in the age of astronauts, having lived long enough to hear a young President speak confidently about landing a man on the moon and bringing him safely back to Earth. Much had changed, he told the cadets that day; the creed of “Duty, Honor, Country” had not. Neither had the courage and devotion of “the American man at arms.” His name and fame are the birthright of every American citizen. In his youth and strength, his love and loyalty, he gave all that mortality can give. He needs no eulogy from me, or from any other man. He has written his own history and written it in red on his enemy’s breast.... In twenty campaigns, on a hundred battlefields, around a thousand campfires, I have witnessed that enduring fortitude, that patriotic self-abnegation, and that invincible determination which have carved his statue in the hearts of his people. From one end of the world to the other, he has drained deep the chalice of courage.

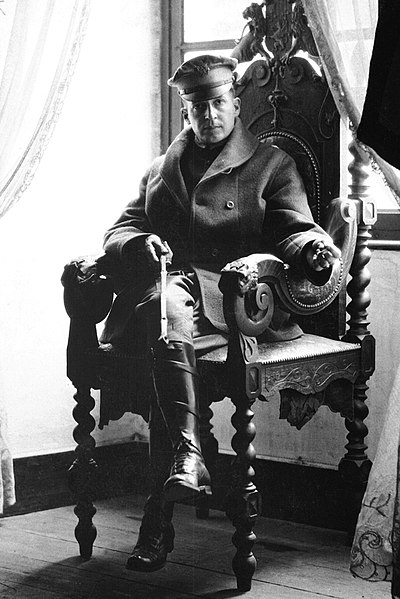

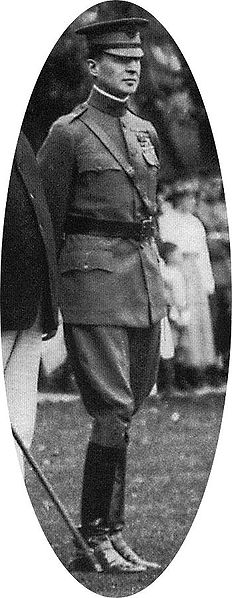

He learned early in life of the soldier’s fierce pride in the honor of his calling. He was the son of General Arthur MacArthur, a Civil War hero who had won the Congressional Medal of Honor at age 18 and later commanded U.S. forces in the Philippines. Along with the sense of honor in military service, he received from his father a treasure of 4,000 books, which he explored in his youth with a keen intellect, devouring information and finding inspiration for that “poetry of imagination” he would often call upon in later years. At West Point, he finished first in his class of 94 cadets, having earned more points than all but two graduates in the history of the academy, one of whom was Robert E. Lee. Yet when he graduated as a second lieutenant in 1903, wrote Manchester, he was, like the rest of the Army, “professionally unprepared for the twentieth century’s wars. He had never fired a machine gun. He knew nothing of barbwire, tanks, or amphibious warfare. All West Point had given him was a lodestar, the academy motto: ‘Duty, Honor, Country.’” Duty, Honor, Country. Those three hallowed words reverently dictate what you ought to be, what you can be, what you will be. They are your rallying points: to build courage when courage seems to fail; to regain faith when there seems to be little cause for faith; to create hope when hope becomes forlorn.... They give you a temperate will, a quality of imagination, a vigor of the emotions, a freshness of the deep springs of life, a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity, an appetite for adventure over love of ease. They create in your heart the sense of wonder, the unfailing hope of what next, and the joy and inspiration of life. They teach you in this way to be an officer and a gentleman. He reached the rank of brigadier general during World War I and was decorated for courage shown in the fighting on the western front, receiving the Distinguished Service Cross twice and the Silver Star seven times. Through “memory’s eye,” he recalled for the cadets that day, the courage and the struggles of the men in his command. As I listened to those songs [of the glee club], in memory’s eye I could see those staggering columns of the First World War, bending under soggy packs on many a weary march, from dripping dusk to drizzling dawn, slogging ankle deep through the mire of shell-pocked roads, to form grimly for the attack, blue-lipped, covered with sludge and mud, chilled by the wind and rain, driving home to their objective, and for many, to the judgment seat of God. I do not know the dignity of their birth, but I do know the glory of their death. They died unquestioning, uncomplaining, with faith in their hearts, and on their lips the hope that we would go on to victory. Always for them: Duty, Honor, Country. Always their blood, and sweat, and tears, as they sought the way and the light and the truth. Nov. 3, 1942: Pushing through New Guinea jungles in a jeep, General Douglas MacArthur inspects the positions and movements of Allied Forces, who would push the Japanese away from Port Moresby and back over the Owen Stanley Mountain range. (AP Photo) # World War II His detractors — and they were legion — would dwell on his considerable ego, noting his fondness for the first person singular pronoun. His most famous words are in the pledge he made from Australia after he had been ordered out of the Philippines, over his protests, before the fall of Corregidor and Bataan in the early months of World War II: “I shall return,” he vowed. When the War Department suggested he change it to “We shall return,” he refused. But MacArthur’s judgment may have been based less on narcissistic pride than on a shrewd understanding of the dramatic effect of his words on the people on the islands. After months of promises of supplies and reinforcements that never came, they had more confidence in the general than in his country. “America has let us down and won’t be trusted,” said Carlos Romulo, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Filipino journalist who had joined MacArthur’s staff as press relations officer and would return as Foreign Secretary in the new Philippines Cabinet. “But the people still have confidence in MacArthur. If he says, he is coming back, he will be believed.” It was two and a half years later when MacArthur did return, landing at Leyte with the Sixth Army in October 1944 to begin the months-long campaign to take back the islands from the Japanese. After wading ashore with Philippines President Sergio Osmena and members of his Cabinet, MacArthur strode to a mobile broadcast unit set up on the beachhead and delivered his message to the people of the Philippines: I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil — soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples.... Rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on.... For your homes and hearth, strike! For future generations of your sons and daughters, strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike! Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of Divine God points the way. Follow in His name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory. By the end of the war, General MacArthur had received a fifth star, along with a Congressional Medal of Honor for actions taken in defense of the Philippines. As the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers, he received the formal surrender of Japan in a ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. Norman Cousins, who interviewed him after the war, was surprised to learn from MacArthur that he had not been consulted about the decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan a month earlier. “He replied that he saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb,” Cousins wrote. “The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” An article in the May-June 1997 issue of the Journal of Historical Review quotes MacArthur as saying, “My staff was unanimous in believing that Japan was on the point of collapse and surrender.” Following the surrender, MacArthur spoke in a broadcast to the American people: A new era is upon us. Even the lesson of victory itself brings with it profound concern, both for our future security and the survival of our civilization. The destructiveness of the war potential, through progressive advances in scientific discovery, has in fact now reached a point which revises the traditional concept of war.... Military alliances, balances of power, leagues of nations have failed, leaving the only path to be by way of the crucible of war.... We have had our last chance. If we don’t now devise some greater and more equitable system, Armageddon will be at our door. The problem is basically theological.... It must be of the spirit if we are to save the flesh. Korea But the uneasy peace that followed World War II was shattered at 4:00 a.m. on June 25, 1950 when 89,000 North Korean troops suddenly crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea. President Truman, without authorization from Congress, sent U.S. forces to fight on the peninsula under MacArthur’s command while insisting, “We are not at war.” Asked at a press conference if it would be correct “to call it a police action under the U.N.,” the President replied. “Yes, that’s exactly what it amounts to.” North Korean forces quickly overran the South Korean capital of Seoul and had U.S. troops pinned down on the perimeter of Pusan in the southeast corner of the peninsula. That set the stage for MacArthur’s unveiling of a bold plan to land forces behind the enemy lines at Inchon and attack the North Koreans from both directions. Much has been made of the general’s flair for the dramatic. “Like King David, Alexander and Joan of Arc,” wrote Manchester, “like virtually all of history’s immortal commanders — he was always performing.” And it required one of his greatest performances to convince the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the landing at Inchon was feasible. At a conference in Tokyo, Admiral Forest Sherman, Chief of Naval Operations, summed up the Navy’s objections: “If every possible geographical and naval handicap were listed — Inchon has ’em all.” Listening to the arguments, MacArthur recalled something his father had told him long ago: “Doug, councils of war breed timidity and defeatism.” As he recounted the event in his memoir,Reminiscences, he responded with the following: The very arguments you have made as to the impracticalities involved will tend to ensure for me the element of surprise. For the enemy commander will reason that no one would be so brash to make such an attempt.... Are you content to let our troops stay in that bloody perimeter like beef cattle in the slaughterhouse? Who will take the responsibility for such a tragedy? Certainly I will not.... Make the wrong decision here — the fatal decision of inertia — and we will be done. I can almost hear the ticking of the second hand of destiny. We must act now or we will die. The room was hushed at the conclusion of his remarks. Finally Admiral Sherman, broke the silence. “Thank you. A great voice in a great cause.” MacArthur got the go-ahead from the nervous chiefs. “I wish I had that man’s optimism,” Sherman said the next day. Admiral James Doyle, who would have to execute the landing, observed: “If MacArthur had gone on stage, we never would have heard of John Barrymore.” Yet the landing was a success and North Korean forces were routed. MacArthur’s troops crossed the 38th parallel and pushed north up toward the Yalu River, the border between North Korea and Communist China. When Chinese units entered the war, driving back the UN forces, Mac-Arthur was frustrated by the restrictions put on military actions by an administration in Washington that was fearful of provoking a wider war with China and possibly bringing the Soviet Union into the conflict. Though Chinese troops had already entered the war by the hundreds of thousands, MacArthur was not allowed to bomb bases and supply depots in Manchuria or the bridges over the Yalu River. (Later he was told he could bomb “the South Korean end” of the bridges, a formidable task since some bridges across the winding river ran east and west, rather than north and south.) Fading Away When MacArthur’s chafing under the restrictions imposed on his military actions became an open secret and a politicial problem for Truman, the President relieved the legendary general of his command in April 1951. MacArthur, then 71, returned home to a hero’s welcome, with a tumultuous reception in San Francisco, followed by record-setting turnouts at parades in his honor in Washington, New York, and other American cities. His 30-minute address to a joint session of Congress — ending with the now-famous refrain from an old Army ballad, “old soldiers never die, they just fade away” — was interrupted with applause 34 times. The applause and the cheers followed him on a cross-country speaking tour, as he inveighed against Truman administration policies both foreign and domestic. It was, wrote Eric Goldman in The Crucial Decade, “the most substantial and noisiest fading away in history.” The nation, meanwhile, shared Mac-Arthur’s frustration over a “no-win” war that would cost more than 54,000 American and more than a million Korean lives before the fighting ended in a stalemate after three years. George Kennan, the former State Department official who was credited with being the “architect” of the global policy of “containment” of communist aggression, described it as “the adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points, corresponding to the shifts and maneuvers of Soviet policy.” MacArthur had a clearer message, one that resonated with the American people: “In war, there is no substitute for victory.” Eventually, he did fade away, leading a life of relative calm and quiet in retirement. He cautioned President Kennedy against committing troops on the Asian mainland. Near the end of his days, he urged President Johnson not to send ground forces into Vietnam. Yet he remained confident, as he told the cadets on that farewell visit, that America’s army would prevail in future conflicts. The long gray line has never failed us. Were you to do so, a million ghosts in olive drab, in brown khaki, in blue and gray, would rise from their white crosses, thundering those magic words: Duty, Honor, Country. This does not mean that you are warmongers. On the contrary, the soldier above all other people, prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war. But always in our ears ring the ominous words of Plato, that wisest of all philosophers: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.” In less than two years, he would join the ranks of the dead. As he looked back that day on a lifetime of service to his country, remembering both victories and defeats, his peroration brought the cadets and others in the audience to their feet at its conclusion: The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here. My days of old have vanished — tone and tint. They have gone glimmering through the dreams of things that were. Their memory is one of wondrous beauty, watered by tears and coaxed and caressed by the smiles of yesterday. I listen vainly, but with thirsty ear, for the witching melody of faint bugles blowing reveille, of far drums beating the long roll. In my dreams I hear again the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange, mournful mutter of the battlefield. But in the evening of my memory always I come back to West Point. Always there echoes and re-echoes: Duty, Honor, Country. Today marks my final roll call with you. But I want you to know that when I cross the river, my last conscious thoughts will be of the Corps, and the Corps, and the Corps. I bid you farewell  Gen. Douglas MacArthur, center, is accompanied by his officers and Sergio Osmena, president of the Philippines in exile, extreme left, as he wades ashore during landing operations at Leyte, Philippines, on October 20, 1944, after U.S. forces recaptured the beach of the Japanese-occupied island. (AP Photo/U.S. Army) September 2, 1945: Gen. Douglas MacArthur signs the Japanese surrender documents aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, left foreground, who surrendered Bataan to the Japanese, and British Lt. Gen. A. E. Percival, next to Wainwright, who surrendered Singapore, observe the ceremony marking the end of World War II. (AP Photo)

To provide historical background: After World War II, the Korean peninsula was temporarily divided along the 38th parallel, with a pro-Communist government in the north and a pro-Western government in the south. Armies from North Korea crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea on June 24, 1950. President Truman's administration immediately committed troops to the United Nations in the effort to move the North Korean army back across the 38th parallel. General Douglas MacArthur, command of the Allied occupation of Japan was extended to include the United Nations troops. The U.N. forces had been forced back to a small perimeter around the southern port city of Pusan. MacArthur succeeded in breaking out of this perimeter in conjunction with the an amphibious landing at Inchon. In a short time the U.N. army crossed the 38th paralled and moved north toward the Yalu River that marked the territorial boundary between China and North Korea. There was an obvious difference of opinion between MacArthur and Truman over the what the point of this military action was. .MacArthur looked for victory as being the defeat of the North Korean army whereas Truman felt this action was one of containment and the aim was not for total victory. There is no doubt that MacArthur aggravated the situation by making public statements that should have first been cleared by superiors. He ignored the chain of command and wrote letters about what the aims of the U.S. should be in Korea even if it risked war with China. As Commander in Chief President Truman fired him. Truman may have acted correctly in that action but surely his actions in restraining the U.N. armed forces from defeating the North Koreans and unifying the country into one Korea should be questioned.  Soviet soldiers on the march in northern Korea in October of 1945. Japan had ruled the Korean peninsula for 35 years, until the end of World War II. At that time, Allied leaders decided to temporarily occupy the country until elections could be held and a government established. Soviet forces occupied the north, while U.S. forces occupied the south. The planned elections did not take place, as the Soviet Union established a communist state in North Korea, and the U.S. set up a pro-western state in South Korea - each state claiming to be sovereign over the entire peninsula. This standoff led to the Korean War in 1950, which ended in 1953 with the signing of an armistice -- but, to this day, the two countries are still technically at war with each other. There should also be no doubt that Truman's decision was one that had an influence on the results of the Vietnam War - and - on other actions taken by our armed forces in other parts of the world. It was the first time the United States essentially lost a war and reflected a weakness in our country's moral fiber, as seen by our enemies, that appears to have done us more harm than good. Looking back over the last fifty plus years, the U.S. has had to maintain a large military force in South Korea and the problem existing between the two Koreas has never been resolved. In fact, we all now know that there exists a much more serious situation involving the possible use of nuclear weapons. It would seem reasonable to view the action President Truman took in allowing the continuation of two Koreas as being wrong. History has demonstrated that appeasement has little success over the long term in the defeat of evil and tyranny.  MacArthur addresses an audience of 50,000 at Soldier Field, Chicago on 25 April 1951. The news of MacArthur's relief was greeted with shock in Japan. The Diet of Japan passed a resolution of gratitude for MacArthur, and the Emperor Hirohito visited him at the embassy in person, the first time a Japanese Emperor had ever visited a foreigner with no standing.The Mainichi Shimbun said: MacArthur's dismissal is the greatest shock since the end of the war. He dealt with the Japanese people not as a conqueror but a great reformer. He was a noble political missionary. What he gave us was not material aid and democratic reform alone, but a new way of life, the freedom and dignity of the individual... We shall continue to love and trust him as one of the Americans who best understood Japan's position.In the Chicago Tribune, Senator Robert Taft called for immediate impeachment proceedings against Truman: President Truman must be impeached and convicted. His hasty and vindictive removal of General MacArthur is the culmination of series of acts which have shown that he is unfit, morally and mentally, for his high office. The American nation has never been in greater danger. It is led by a fool who is surrounded by knaves.Newspapers like the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times opined that MacArthur's "hasty and vindictive" relief was due to foreign pressure, particularly from the United Kingdom and the British socialists in Attlee's government.[The Republican Party whip, Senator Kenneth S. Wherry, charged that the relief was the result of pressure from "the Socialist Government of Great Britain." MacArthur flew back to the United States, a country he had not seen in years. When he reached San Francisco he was greeted by the commander of the Sixth United States Army, Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer. MacArthur received a parade there that was attended by 500,000 people. He was greeted on arrival at Washington National Airport on April 19 by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and General Jonathan Wainwright. Truman sent Vaughan as his representative. which was seen as a slight, as Vaughan was despised by the public and professional soldiers alike as a corrupt crony. "It was a shameful thing to fire MacArthur, and even more shameful to send Vaughan," one member of the public wrote to Truman. MacArthur addressed a joint session of Congress where he delivered his famous "Old Soldiers Never Die" speech, in which he declared: Efforts have been made to distort my position. It has been said in effect that I was a warmonger. Nothing could be further from the truth. I know war as few other men now living know it, and nothing to me—and nothing to me is more revolting. I have long advocated its complete abolition, as its very destructiveness on both friend and foe has rendered it useless as a means of settling international disputes... But once war is forced upon us, there is no other alternative than to apply every available means to bring it to a swift end. War's very object is victory, not prolonged indecision. In war there can be no substitute for victory. In response, the Pentagon issued a press release noting that "the action taken by the President in relieving General MacArthur was based upon the unanimous recommendations of the President's principal civilian and military advisers including the Joint Chiefs of Staff." Afterwards, MacArthur flew to New York City where he received the largest ticker-tape parade in history up to that time. He also visited Chicago and Milwaukee, where he addressed large rallies. In May and June 1951, the Senate Armed Services Committee and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held "an inquiry into the military situation in the Far East and the facts surrounding the relief of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur." Because of the sensitive political and military topics being discussed, the inquiry was held in closed session, and only a heavily censored transcript was made public until 1973. The two committees were jointly chaired by Senator Richard Russell, Jr. Fourteen witnesses were called: MacArthur, Marshall, Bradley, Collins, Vandenberg, Sherman, Adrian S. Fisher, Acheson, Wedemeyer, Johnson, Oscar C. Badger II, Patrick J. Hurley, and David C. Barr and O'Donnell. The testimony of Marshall and the Joint Chiefs rebutted many of MacArthur's arguments. Marshall emphatically declared that there had been no disagreement between himself, the President, and the Joint Chiefs. However, it also exposed their own timidity in dealing with MacArthur, and that they had not always kept him fully informed. Vandenberg questioned whether the air force could be effective against targets in Manchuria, while Bradley noted that the Communists were also waging limited war in Korea, having not attacked UN airbases or ports, or their own "privileged sanctuary" in Japan. Their judgement was that it was not worth it to expand the war, although they conceded that they were prepared to do so if the Communists escalated the conflict, or if no willingness to negotiate was forthcoming. They also disagreed with MacArthur's assessment of the effectiveness of the South Korean and Chinese Nationalist forces. Bradley said: Red China is not the powerful nation seeking to dominate the world. Frankly, in the opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this strategy would involve us in the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.The committees concluded that "the removal of General MacArthur was within the constitutional powers of the President but the circumstances were a shock to national pride."[169] They also found that "there was no serious disagreement between General MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs of Staff as to military strategy."[170] They recommended that "the United States should never again become involved in war without the consent of the Congress." Polls showed that the majority of the public still disapproved of Truman's decision to relieve MacArthur, and were more inclined to agree with MacArthur than with Bradley or Marshall.Truman's approval rating fell to 23 percent in mid-1951, which was lower than Richard Nixon's low of 25 per cent during the Watergate Scandal in 1974, and Lyndon Johnson's of 28 percent at the height of the Vietnam War in 1968. As of 2011, it remains the lowest Gallup Poll approval rating recorded by any serving president. The increasingly unpopular war in Korea dragged on, and the Truman administration was beset with a series of corruption scandals. He eventually decided not to run for re-election. Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic candidate in the 1952 presidential election, attempted to distance himself from the President as much as possible. The election was won by the Republican candidate, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose administration ramped up the pressure on the Chinese in Korea with conventional bombing and renewed threats of using nuclear weapons. Coupled with a more favorable international political climate in the wake of the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, this led the Chinese and North Koreans to agree to terms. The belief that the threat of nuclear weapons played an important part in the outcome would lead to their threatened use against China on a number of occasions during the 1950s. As a result of their support of Truman, the Joint Chiefs became viewed as politically tainted. Senator Taft regarded Bradley in particular with suspicion, due to Bradley's focus on Europe at the expense of Asia. Taft urged Eisenhower to replace the chiefs as soon as possible. First to go was Vandenberg, who had terminal cancer and had already announced plans to retire. On 7 May 1953, Eisenhower announced that he would be replaced by General Nathan Twining. Soon after it was announced that Bradley would be replaced by Admiral Arthur W. Radford, the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Command, Collins would be succeeded by Ridgway, and Admiral William Fechteler, who had become CNO on the death of Sherman in July 1951, by AdmiralRobert B. Carney The relief of MacArthur cast a long shadow over American civil-military relations. When Lyndon Johnson met with General William Westmoreland in Honolulu in 1966, he told him: "General, I have a lot riding on you. I hope you don't pull a MacArthur on me." or his part, Westmoreland and his senior colleagues were eager to avoid any hint of dissent or challenge to presidential authority. This came at a high price. In his 1998 book Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, then-Lieutenant Colonel (now Major General) H. R. McMaster argued that the Joint Chiefs failed in their duty to provide the President, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara or Congress with frank and fearless professional advice.[179] This book was an influential one; the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the time, General Hugh Shelton, gave copies to every four-star officer in the military. In February 2012, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel L. Davis published a report entitled "Dereliction of Duty II" in which he criticized senior military commanders for misleading Congress about the war in Afghanistan,[181] especially General David Petraeus, whom he described as "a real war hero— maybe even on the same plane as Patton, MacArthur, and Eisenhower". President Truman pins the Distinguished Service Medal with four oak leaf clusters on the shirt of General Douglas MacArthur during a ceremony at the airstrip on Wake Island, in this Oct. 14, 1950, file photo. In the center is John J. Muccio, United States ambassador to Korea, who was decorated with a Medal of Merit. According to a letter sent by Muccio to the State Department, U.S. soldiers would fire on refugees if they approached U.S. lines. The letter referred to a policy set down on July 25, 1950, the night before members of the 7th U.S. Cavalry began killing South Korean refugees at the village of No Gun Ri. Four LST's unload men and equipment on beach in Inchon on Sept. 15, 1950. Three of LST's shown are right to left: LST-715, LST-845, and LST-611. (AP Photo) This homeless brother and sister make a vain attempt to keep warm near a small fire in the Seoul Railroad Yards on Dec. 29, 1950. (AP Photo) A US 25th Div. Inf. gets set to heave a grenade at enemy sniper hidden in a village 20 miles north Taegu on Naktong River front in Korea on August 29, 1950. (AP Photo) Weighted down with sundry items ranging from guns and trench shovels to a radio set, Sgt. Derrick Deamer, left, and Pvt. Clem Williams wear full battle gear as they chat on British sector of Korea?s Naktong River front in South Korea on Sept. 14, 1950. Both are with British forces fighting with United Nations? troops against the Chinese Communist troops. (AP Photo/GH) A bazooka team fires at enemy tanks near the front lines in the battle for South Korea on July 5, 1950. (AP Photo) Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander-in-chief of United Nations Forces, on the bridge of the USS McKinley on his arrival at Inchon Harbor in September, 1950. Standing left to right are: Vice Admiral Arthur D. Strubble, Commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet; Brig. Gen. E.K. Wright, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3 Far East command and Major Gen. Edward M. Almond, Commanding General, 10th corps. (AP Photo) I'm still wondering if anyone can tell me what threat Germany was to the U.S. in 1941-42? Why "Europe First"??? Could it have been to help out Stalin’s regime at the expense of American lives? I just don't see the need for Europe first being in the U.S. strategic intrest at that time. I'd be happy if someone could explain to me how it was strategically better FOR THE USA to be involved in a European war when we were first attacked in the Pacific. Churchill came away from the Atlantic Conference on August 14, 1941, observing the "astonishing depth of Roosevelt's intense desire for war." Before we entered the war, FDR sent a delegation to the Vatican to get the Pope to endorse Godless communism - he refused. With lend-lease, a.k.a. Lenin-lease, before Pearl Harbor FDR pressed his aides to allocate and speed shipments to the Soviet Union in the strongest possible way. FDR exerted frenetic personal devotion to the cause of lend-lease to the communists, distinctly favoring Russia over Britain (and US) and if you read page 549 volume 3 of The Secret Diaries of Harold Ickes, Ickes makes it clear that in a choice between England and Russia FDR would have abandoned England: "if the (public) attitude had been one of angry suspicion or even resentment, we would have been confronted with the alternative of abandoning Great Britian or accepting communism..." On August 1, 1941 FDR said about planes for Russia, "we must get 'em, even if it necessary to take from our own troops." Ickes said "we ought to come pretty close to stripping ourselves in view of Russian aid." The US sent 150 P-40's (the newest) when we were woefully short. In 1944 Churchill publicly complained about Britain being treated worse than the Soviet Union (in 1943 we sent 5,000 planes to Russia; overall we sent 20,000 planes and 400,000 trucks - twice as many as they had had before the war, 9 million pairs of boots, complete factories as part of $11 billion in aid that was never expected to be paid back). FDR's oil embargo of Japan forcing them South to take oil-rich Dutch Indonesia, is incomprehensible unless you realize FDR did it to relieve Japanese military threats to the Soviet Union. |

Billows of smoke from burning buildings pour over the wall which encloses Manila's Intramuros district, sometime in 1942. (AP Photo) #

American soldiers line up as they surrender their arms to the Japanese at the naval base of Mariveles on Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines in April of 1942. (AP Photo) #

American soldiers line up as they surrender their arms to the Japanese at the naval base of Mariveles on Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines in April of 1942. (AP Photo) #

Japanese soldiers stand guard over American war prisoners just before the start of the "Bataan Death March" in 1942. This photograph was stolen from the Japanese during Japan's three-year occupation. (AP Photo/U.S. Marine Corps) #

Japanese soldiers stand guard over American war prisoners just before the start of the "Bataan Death March" in 1942. This photograph was stolen from the Japanese during Japan's three-year occupation. (AP Photo/U.S. Marine Corps) #

In his diary, Secretary Stimson noted receipt of the "very gloomy study" from the War Plans Division. In Stimson's words, the report encouraged the senior leadership to recognize that "it would be impossible for us to relieve MacArthur and we might as well make up our minds about it." However, either Stimson couldn't make up his mind or he was unwilling to confront MacArthur and others with the growing evidence that supported Eisenhower's conclusion. The Secretary went on to write, "It is a bad kind of paper to be lying around the War Department at this time. Everybody knows the chances are against our getting relief to him [MacArthur] but there is no use in saying so before hand'" (emphasis added). Reflecting Stimson's attitude, Marshall apparently never shared Eisenhower's report with MacArthur nor made its contents public. D. ClaytonJames, the respected biographer of Douglas MacArthur, likened Roosevelt'sand Marshall's hopeful words to the false encouragement given by some physicians to dying patients. The President's and Chief of Staff's intent, assurmised by James, was to brace the Philippine defenders to fight longer than they might have if they were told the truth. According to James, promisesmade by Roosevelt and Marshall deceived MacArthur and were "an insult to the garrison's bravery and determination. General MacArthur may have initially been duped into believing thecheery news from his superiors. But it seems highly unlikely that the savvy MacArthur could have long been deluded as the weeks dragged on and convoys destined for the Philippines were diverted to Australia or Hawaii. Historian Louis Morton, whose book The Fall of the Philippines is recognized as the definitivework on the topic, notes that USAFFE headquarters was indeed aware that the promised help was unlikely to reach Philippine shores in time. Those who knew the full story told no one. When one American colonel asked a friend on theUSAFFE staff when relief might arrive, the staff officer's eyes "went pokerblank and his teeth bit his lips into a grim thin line." The troops were encouraged to assume help was weeks, perhaps only days away.MacArthur hammered General Marshall with repeated early messages insisting that the blockade could be broken and demanding that the Navy increase its efforts. Marshall, however, acknowledged on 17 January. 1942 that the only reason the Navy should continue to challenge the Japanese blockade was for "the moral effect occasional small shipments might have on the beleaguered forces."lf MacArthur eventually saw the grim reality of no meaningful relief coming from the United States. By February, his cables to Washington began to raise issues concerning the fate of Philippine President Quezon once the Islands were lost to the Japanese. However, General MacArthur did nothing to alter the original picture he painted for his troops. Thousands of malnourished soldiers, riddled with intestinal disease, clung to the belief that if they could hold out for a short time, they would be saved. There is no evidence that MacArthur and General Jonathan Wainwright had a frank discussion of the relief situation as the latter took charge of the Filipino-American force. The change of command was a hurried affair,with MacArthur promising Wainwright to "come back as soon as I can with as much as I can." Wainwright's reply, which he came to regret, was, "I'll be here on Bataan ifI'm alive,',Impact on the SoldiersAs word of Douglas MacArthur's escape to Australia spread among American and Filipino troops, morale plummeted. For some, it was a sign that they had been abandoned to face death or capture by the brutal Japanese.While many experienced this disillusionment, others believed the charismatic MacArthur would return from Australia posthaste leading the relief force.Indeed, once in Australia, MacArthur's first message was again one of hope. This time he said that the relief of the Philippines was his primary mission. In a pledge that was continuously broadcast and printed on everything fromletterheads to chewing gum wrappers, the general simply stated, "I made it through and I shall return. There is ample evidence that soldiers placed great stock in MacArthur's renewed pledge from Australia. When "Skinny" Wainwright made the fateful decision to surrender the entire Philippine command in May 1942,

Regardless of how the blame is spread for this prevarication, the fact is that Roosevelt, Stimson, Marshall, and MacArthur all refused to level with the troops. Failing to inform the soldiers that substantial relief of the Philippines was several months or even years away may be described as an exaggeration or half-truth rather than a lie. Whatever label given to this false promise, it was a breech of ethical standards. Soldiers in the Philippines fought gallantly and held out longer than expected, but at the cost of distrust, bitterness, and resentment toward their leaders and government. Professional Ethics, Military Necessity, and Exceptions to the Rule. The implicit question posed by this episode-when is lying to the troops justified?-is likely to elicit an immediate and resounding "Never!"

from most military officers. As retired Major General Clay Buckingham wrote in an essay on ethics, the oath of a professional officer should be "to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.,,20 Half-truths or deceptions do not fall within the military's concept of honor and integrity. Not surprisingly, a plethora of books and articles on military ethics echo this view, using vignettes or case studies to illustrate the critical nature of honesty in the military.

While the US Army has never published a formal code of ethics, Field Manual 1 00-1, The Army, does devote a Chapter to the professional Army ethic and individual values. Among the key values listed is candor, described as "honesty and fidelity to the truth .... Soldiers must at all times demand honesty and candor from themselves and from their fellow soldiers.""

The values espoused in FM 100-1 are a distillation of ethical standards and moral beliefs that have been operative in the US Army from its conception. Lying and deception as devices to motivate soldiers to accomplish the mission were ethically wrong in 1942 just as they are today. True, anyone

can concoct a hypothetical situation where a lie or half-truth may be used to save an innocent life. But a moral dilemma that offers lying as the only means to preserve life is extremely rare. Building morale on a deception or motivatiing soldiers with a lie remains unethical. Did our towering leaders of World War II-Roosevelt, Stimson, Marshall, MacArthur-set a course knowing their acts were unethical or, as more likely, did they hold to some other ethical precept they felt to be more compelling than honesty and candor? In questions of morality and ethics, even the most sacred values are challenged when they collide with other bedrock principles. The promise of help to the Philippines is a case in point. America's

To appreciate this argument it is important to recall the military and political situation in the Philippines. In the first months of America's entry

into World War II, victory over Japan was far from certain. For Marshall and Stimson, and particularly for the nation's political leader, Franklin Roosevelt, the battle for the Philippines was a symbol of America's resolve to stay in the

fight despite repeated setbacks in the Pacific. It was feared that early capitulation or mass desertions in the Philippines would have great moral and political significance for the nation. This can be inferred from the revealing and startling passage Secretary Stimson wrote in his diary on the eve of Bataan's surrender:

[It has been suggested] that we should not order a fight to the bitter end [in the Philippines] because that would mean the Japanese would massacre everyone there. McCloy, Eisenhower, and I in thinking it over agreed that ... even if such

a bitter end had to be, it would be probably better for the cause of the country in the end than would surrender. Obviously, the War Department was willing to go to great lengths to keep Wainwright and his troops in the fight. There was apparently the presumption that final victory over Japan would be hastened and morale at home bolstered by frustrating the enemy's timetable in the Philippines. However, the United States lacked sufficient war materiel to ship to the islands and had no means to pierce the blockade. Roosevelt, Stimson, and Marshall therefore chose to send the brave defenders words of hope regarding relief efforts in order to encourage them to hold on as long as possible.

On a more basic level was the effect MacArthur's promises had on individual soldiers. Had the troops on Bataan been told the truth and dealt with in a forthright manner, they might have been better prepared psychologically for the fate that surely awaited them. Perhaps some who perished during brutal Japanese captivity would have survived. We will never know, but the possibility alone makes this a point worthy of consideration by today's leaders.

American prisoners of war carry their wounded and sick during the Bataan Death March in April of 1942. This photo was taken from the Japanese during their three year occupation of the Philippines. (AP Photo/U.S. Army)

The defense of the Philippines cannot be understood in terms of conventional military strategy. In those terms it was one incomprehensible blunder after another, done with due deliberation and afterward profusely rewarded. Just as Clauswitz said war is politics by other means, the sacrifice of the Philippines can only be understood in the larger political context. Analysis of local decisions by MacArthur, miss the point that FDR was actually calling the shots. His motivations, not MacArthur's are at issue. The sacrifice of the 31,095 Americans and 80 thousand Filipino troops with 26 thousand refugees on Bataan is a separate issue from the sacrifice of the Army Air Corps at Clark and Iba.

Solemnly promising the nation his utmost effort to keep the country neutral, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is shown as he addressed the nation by radio from the White House in Washington, Sept. 3, 1939. In the years leading up to the war, the U.S. Congress passed several Neutrality Acts, pledging to stay (officially) out of the conflict. (AP Photo)

The bombers were sacrificed, not only to facilitate the loss of the Philippines, but more immediately to sucker Hitler into declaring war on the United States and events in the Philippines are analogous to Pearl Harbor which happened the same day. However, Hitler did declare war on December 11th and therefore obviously the sacrifice of Bataan proper springs from other motives. To understand Roosevelt's strategy we have to ask a very basic question: Cui bono? "Who benefits?" Who benefited from Japan's temporary ascendancy and the war dragging on? It was obvious that when the Japanese Empire collapsed that there would be a power vacuum in Asia. The ultimate question of the Pacific War was who would fill that vacuum. Who would take China? Roosevelt wanted Russia to fill the vacuum (cf. his actions at Yalta and How the Far East Was Lost, Dr. Anthony Kubek, 1963) and therefore had to prolong the war so the Soviet Union could pick up the pieces. Because the Soviet Union had its hands full fighting Germany and could not dominate Asia until the war in Europe was under control, delay in the defeat of Japan was necessary. Bataan was a pawn in a larger game. The Battling Bastards of Bataan never understood enough to ask the critical question - "who was their real enemy?" It was Franklin Roosevelt.

No comments:

Post a Comment