The U.S. offensive against the North Vietnamese near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), that lasted from August 3 to October 27, 1966. An estimated 1,329 Americans were killed during the operation. |

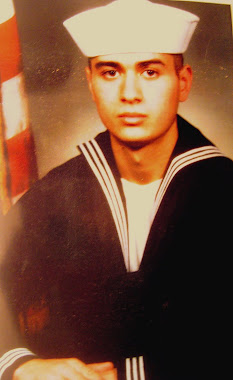

'60s Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie, a blood-stained bandage tied around his head — appears to be inexorably drawn to a stricken comrade. Here, in one astonishing frame, we witness tenderness and terror, desolation and fellowship — and, perhaps above all, we encounter the power of a simple human gesture to transform, if only for a moment, an utterly inhuman landscape. The longer we consider that scarred landscape, however, the more sinister — and unfathomable — it grows. The deep, ubiquitous mud slathered, it seems, on simply everything; trees ripped to jagged stumps by artillery shells and rifle fire; human figures distorted by wounds, bandages, helmets, flak jackets; and, perhaps most unbearably, the evident normalcy of it all for the young Americans gathered there in the aftermath of a firefight on a godforsaken hilltop thousands of miles from home. Americans remember Vietnam War 40 years after last US troops were pulled from bloody battlefield. It's been forty years since the last of America's troops left Vietnam. While the fall of Saigon two years later - with its unforgettable images of frantic helicopter evacuations - is remembered as the final day of the Vietnam War, Friday marks an anniversary that holds greater meaning for the Americans who fought, protested or otherwise lived the war.As the remaining US soldiers boarded their flights home on March 29, 1973, as like many who went before them, they were advised to change into civilian clothes because of fears they would be accosted by protesters after they landed.In the four decades since then, many veterans have embarked on careers, raised families and in many cases counseled a younger generation emerging from two other faraway wars. Exit: In this March 29, 1973 photo, Camp Alpha, Uncle Sam's out processing center, was chaos in Saigon Many who fought in Vietnam are encouraged by changes they see. The U.S. has a volunteer military these days, not a draft, and the troops coming home aren't derided for their service. People know what PTSD stands for, and they're insisting that the government take care of soldiers suffering from it and other injuries from Iraq and Afghanistan. Former Air Force Sgt. Howard Kern, who lives in central Ohio near Newark, spent a year in Vietnam before returning home in 1968.He said that for a long time he refused to wear any service ribbons associating him with southeast Asia and he didn't even his tell his wife until a couple of years after they married that he had served in Vietnam.He said she was supportive of his war service and subsequent decision to go back to the Air Force to serve another 18 years. Boarding: In a curious ending to a bizarre conflict, American troops boarded jets under the watchful eyes of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong observers in Saigon Kern said that when he flew back from Vietnam with other service members, they were told to change out of uniform and into civilian clothes while they were still on the airplane in case they encountered protesters. 'What stands out most about everything is that before I went and after I got back, the news media only showed the bad things the military was doing over there and the body counts,' said Kern, now 66. 'A lot of combat troops would give their c rations to Vietnamese children, but you never saw anything about that - you never saw all the good that GIs did over there.' Kern, an administrative assistant at the Licking County Veterans' Service Commission, said the public's attitude is a lot better toward veterans coming home for Iraq and Afghanistan - something he attributes in part to Vietnam veterans. 'We're the ones that greet these soldiers at the airports. We're the ones who help with parades and stand alongside the road when they come back and applaud them and salute them,' he said. Chaos: Lines of bored soldiers snaked through customs and briefing rooms as they left Vietnam He said that while the public 'might condemn war today, they don't condemn the warriors.' 'I think the way the public is treating these kids today is a great thing,' Kern said. 'I wish they had treated us that way.' But he still worries about the toll that multiple tours can take on service members. 'When we went over there, you came home when your tour was over and didn't go back unless you volunteered. They are sending GIs back now maybe five or seven times, and that's way too much for a combat veteran,' he said. He remembers feeling glad when the last troops left Vietnam, but was sad to see Saigon fall two years later. 'Vietnam was a very beautiful country, and I felt sorry for the people there,' he said. For a Vietnamese businessman who helped the U.S. government, a rising panic set in when the last combat troops left the country. A married father, Tony Lam was 36 on March 29, 1973 and had spent much of the war furnishing dehydrated rice to South Vietnamese troops. He also ran a fish meal plant and a refrigerated shipping business that exported shrimp. Long war: Most were thrilled the Vietnam War, which had lasted more than a decade, was over for the US (photo from 1965) As Lam, now 76, watched American forces dwindle and then disappear, he felt a sence of panic started to build within him. His close association with the Americans was well-known and he needed to get out - and get his family out - or risk being tagged as a spy and thrown into a Communist prison. He watched as South Vietnamese commanders fled, leaving whole battalions without a leader. 'We had no chance of surviving under the Communist invasion there. We were very much worried about the safety of our family, the safety of other people,' he said this week from his adopted home in Westminster, California. But Lam wouldn't leave for nearly two more years, driven to stay by his love of his country and his belief that Vietnam and its economy would recover. When Lam did leave, on April 21, 1975, it was aboard a packed C-130 that departed just as Saigon was about to fall. He had already worked for 24 hours at the airport to get others out after seeing his wife and two young children off to safety in the Philippines. Gruesome: The Vietnam War was wisely televised in the US and returning troops were targeted by protestors (photo from 1969) War: In this 03 Aug 1965 photo, an aged woman injured by a U.S.-Vietnamese air strike on a Buddist monastery 40 miles southeast of Saigon is carried to a hospital by airborne private Carl Champ of Furgitsville, West Virginia Like many who came home from the war, Reynolds is haunted by the fact he survived Vietnam when thousands more didn't. Encountering war protesters after returning home made the readjustment to civilian life more difficult. 'I was literally spat on in Chicago in the airport,' he said. 'No one spoke out in my favor.' Reynolds said the lingering survivor's guilt and the rude reception back home are the main reasons he spends much of his time now working with veteran's groups to help others obtain medical benefits. He also acts as an advocate on veterans' issues, a role that landed him a spot on the program at a 40th anniversary ceremony planned for Friday in Huntsville, Alabama. It took a long time for Reynolds to acknowledge his past, though. For years after the war, Reynolds said, he didn't include his Vietnam service on his resume and rarely discussed it with anyone. 'A lot of that I blocked out of my memory. I almost never talk about my Vietnam experience other than to say, "I was there," even to my family,' he said. Many who fought in the war bore resentment to the other side for years, after the brutality they witnessed. Fear: In this 15 May 1965 photo, a Vietnamese mother and her son hide in bushes near Le My to escape fighting as U.S. Marines go past after clearing the village of Viet Cong forces But a former North Vietnamese soldier, Ho Van Minh, says he bears no ill will towards his former enemy. He says he heard about the American combat troop withdrawal during a weekly meeting with his commanders in the battlefields of southern Vietnam. The news gave the northern forces fresh hope of victory, but the worst of the war was still to come for Minh: The 77-year-old lost his right leg to a land mine while advancing on Saigon, just a month before that city fell. 'The news of the withdrawal gave us more strength to fight,' Minh said Thursday, after touring a museum in the capital, Hanoi, devoted to the Vietnamese victory and home to captured American tanks and destroyed aircraft. 'The U.S. left behind a weak South Vietnam army. Our spirits was so high and we all believed that Saigon would be liberated soon,' he said. Minh, who was on a two-week tour of northern Vietnam with other veterans, said he doesn't harbor resentment to the American soldiers even though much of the country was destroyed and an estimated three million Vietnamese died. Bored: In this March 27, 1973 photo, an American GI takes a nap atop his luggage as he and other troops wait to begin out processing at Camp Alpha in Saigon If he met an American veteran now he says, 'I would not feel angry; instead I would extend my sympathy to them because they were sent to fight in Vietnam against their will.' But on his actions, he has no regrets. 'If someone comes to destroy your house, you have to stand up to fight.' Friday's anniversary is an important day for Marine Corps Capt. James H. Warner who just two weeks before the last troops left was freed from North Vietnamese confinement after nearly 5 1/2 years as a prisoner of war. He said those years of forced labor and interrogation reinforced his conviction that the United States was right to confront the spread of communism. The past 40 years have proven that free enterprise is the key to prosperity, Warner said in an interview on Thursday at a coffee shop near his home in Rohrersville, Md., about 60 miles from Washington. He said American ideals ultimately prevailed, even if our methods weren't as effective as they could have been. Don't forget the flag: In this March 29, 1973 file photo, the American flag is furled at a ceremony marking official deactivation of the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam (MACV) in Saigon, after more than 11 years in South Vietnam 'China has ditched socialism and gone in favor of improving their economy, and the same with Vietnam. The Berlin Wall is gone. So essentially, we won,' he said. 'We could have won faster if we had been a little more aggressive about pushing our ideas instead of just fighting.' Warner, 72, was the avionics officer in a Marine Corps attack squadron when his fighter plane was shot down north of the Demilitarized Zone in October 1967. He said the communist-made goods he was issued as a prisoner, including razor blades and East German-made shovels, were inferior products that bolstered his resolve. 'It was worth it,' he said. A native of Ypsilanti, Mich., Warner went on to a career in law in government service. He is a member of the Republican Central Committee of Washington County, Md. Another story comes from Denis Gray, who witnessed the Vietnam War twice - as an Army captain stationed in Saigon from 1970 to 1971 for a U.S. military intelligence unit, and again as a reporter at the start of a 40-year career with the Associated Press. Getting out: In this March 27, 1973 photo, surrounded by luggage of other departing GIs, U.S. Air Force airman reads paperback novel as he waits to begin processing at Camp Alpha on Saigon's Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon as troop withdraw 'Saigon in 1970-71 was full of American soldiers. It had a certain kind of vibe. There were the usual clubs, and the bars were going wild,' Gray recalled. 'Some parts of the city were very, very Americanized.' Gray's unit was helping to prepare for the troop pullout by turning over supplies and projects to the South Vietnamese during a period that Washington viewed as the final phase of the war. But morale among soldiers was low, reinforced by a feeling that the U.S. was leaving without finishing its job. 'Personally, I came to Vietnam and the military wanting to believe that I was in a - maybe not a just war but a - war that might have to be fought,' Gray said. 'Toward the end of it, myself and most of my fellow officers, and the men we were commanding didn't quite believe that ... so that made the situation really complex.' After his one-year service in Saigon ended in 1971, Gray returned home to Connecticut and got a job with the AP in Albany, N.Y. But he was soon posted to Indochina, and returned to Saigon in August 1973 - four months after the U.S. troops withdrew from Vietnam - to discover a different city. Viet Cong: In this March 28, 1973 photo, a Viet Cong observer of the Four Party Joint Military Commission counts U.S. troops as they prepare to board jet aircraft at Saigon's Tan Son Nhut airport 'The aggressiveness that militaries bring to any place they go - that was all gone,' he said. A small American presence remained, mostly diplomats, advisers and aid workers but the bulk of troops had left. The war between U.S.-allied South Vietnam and communist North Vietnam was continuing, and it was still two years before the fall of Saigon to the communist forces. 'There was certainly no panic or chaos - that came much later in '74, '75. But certainly it was a city with a lot of anxiety in it.' The Vietnam War was the first of many wars Gray witnessed. As AP's Bangkok bureau chief for more than 30 years, Gray has covered wars in Cambodia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, Rwanda, Kosovo, and 'many, many insurgencies along the way.' 'I don't love war, I hate it,' Gray said. '(But) when there have been other conflicts, I've been asked to go. So, it was definitely the shaping event of my professional life.' Harry Prestanski, 65, of West Chester, Ohio, served 16 months as a Marine in Vietnam and remembers having to celebrate his 21st birthday there. Air force: In this March 27, 1973 photo, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese members of the joint military commission, foreground, shoot photos of U.S. troops as they board an Air Force plane for the flight home from Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Air Base He is now retired from a career in public relations and spends a lot of time as an advocate for veterans, speaking to various organizations and trying to help veterans who are looking for jobs. 'The one thing I would tell those coming back today is to seek out other veterans and share their experiences,' he said. 'There are so many who will work with veterans and try to help them - so many opportunities that weren't there when we came back.' He says that even though the recent wars are different in some ways from Vietnam, those serving in any war go through some of the same experiences. 'One of the most difficult things I ever had to do was to sit down with the mother of a friend of mine who didn't come back and try to console her while outside her office there were people protesting the Vietnam War,' Prestanski said. He said the public's response to veterans is not what it was 40 years ago and credits Vietnam veterans for helping with that. Over: In this April 2, 1973 photo, President Richard Nixon and South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu are in profile as they listen to national anthems during arrival ceremonies for Thieu at the Western White House in San Clemente, Calif 'When we served, we were viewed as part of the problem,' he said. 'One thing about Vietnam veterans is that - almost to the man - we want to make sure that never happens to those serving today. We welcome them back and go out of our way to airports to wish them well when they leave.' He said some of the positive things that came out of his war service were the leadership skills and confidence he gained that helped him when he came back. 'I felt like I could take on the world, he said. But the war didn't just affect those who were living it, it also deeply affected the children of veterans, many of whom were struggling to deal with the trauma of what they'd experienced. Zach Boatright's father served 21 years in the Air Force and he spent his childhood rubbing shoulders with Vietnam vets who lived and worked on Edwards Air Force Base in California's Mojave Desert, where he grew up. Yet Boatright, 27, said the war has little resonance with him. Welcome: In this Thursday, March 30, 1973 photo, the last 55 troops to leave Vietnam debark their Air Force C-141 at Travis Air Force Base 'We have a new defining moment. 9/11 is everyone's new defining moment now,' he said of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on U.S. soil. Boatright, who was 16 when the planes struck the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, said two of his best friends are now Air Force pilots serving in Afghanistan. He decided not to pursue the military and recently graduated from Fresno State University with a degree in recreation administration. People back home are more supportive of today's troops, Boatright said, because the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are linked in Americans' minds with those attacks. Improved military technology and no military draft also makes the fighting seem remote to those who don't have loved ones enlisted, he said. 'Because 9/11 happened, anything since then is kind of justified. If you're like, "We're doing that because of this" then it makes people feel better about the whole situation,' said Boatright, who's working at a Starbucks in the Orange County suburbs while deciding whether to pursue a master's degree in history. | Robert J. Lee was a US Army volunteer in the Infantry during the Vietnam war. The 4th Infantry Division deployed from Fort Lewis to Camp Holloway, Pleiku, Vietnam on September 25, 1966 and served more than four years, returning to Fort Carson, Colorado on December 8, 1970. Two brigades operated in the Central Highlands/II Corps Zone, but its 3rd Brigade, including the division's armor battalion, was sent to Tay Ninh Province northwest of Saigon to take part in Operation Attleboro (September to November, 1966), and later Operation Junction City (February to May, 1967), both in War Zone C. After nearly a year of combat, the 3rd Brigade's battalions officially became part of the 25th Infantry Division in exchange for the battalions of the 25th's 3rd Brigade, then in Quang Ngai Province as part of the division-sized Task Force Oregon. Throughout its service in Vietnam the division conducted combat operations in the western Central Highlands along the border between Cambodia and Vietnam. By 1967 October, US intelligence reported that PAVN was withdrawing regiments from the Pleiku area to join those in Kontum Province, thereby dramatically increasing the strength of the local forces to that of a full division. In response, the 4th Infantry, began moving in more forces. On 29 October, the remainder of the 173d Airborne Brigade was brought in as reinforcement. They were joined by more ARVN units. In addition, the division was assisted by the 40th Artillery Regiment as well. The goal of these units was the taking of Dak To and the destruction of a "large American unit." This intelligence was bolstered by other means. The actions around Dak To were part of an overall strategy devised by the PAVN leadership, primarily that of General Vo Nguyen Giap. The goal of North Vietnamese operations in the area, according to a captured document from the B-3 Front Command, was "to annihilate a major US element in order to force the enemy to deploy as many additional troops to the western highlands as possible. To Hell and Back Robert Lee during the Battle of Dak To. Fighting erupted on 3 and 4 November when companies of the 4th Infantry bumped into PAVN defensive positions. Two days later the same thing occurred to elements of the 173rd. The following morning Bravo Company was relieved by C/4/503, supported by two companies of D/1/503. Task Force Black (as the combined unit was known) left Hill 823 and moved out on patrol. Before 0800 on 11 November, the force was ambushed by the 3rd Battalion, PAVN 174th Regiment[4] and had to fight for its life. C/4/503 drew the job of going to the relief of task force. They encountered fire from all sides, but they made it, reaching the trapped men at 1537. US losses were 20 killed, 154 wounded, and two missing. The commanding officer reported an enemy body count of 80, but was told to go out and count again. He then reported back that 116 enemy soldiers had been killed. He later stated that "If you lost so many people killed and wounded, you had to have something to show for it

Reaching Out: Wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie (center, with bandaged head) reaches toward a stricken comrade after a fierce firefight

Battle: A dazed, wounded American Marine gets bandaged during Operation Prairie

Fallen: Four Marines recover the body of Marine fire team leader Leland Hammond as their company comes under fire near Hill 484. (At right is the French-born photojournalist Catherine Leroy)

Burrows himself suffered a tragic end as he worked on the front lines, he was killed on February 10, 1971 over Laos when his helicopter was shot down. He was 44-years-old.

Fellow photographers Henri Huet, 43, of the Associated Press, Kent Potter, 23, of United Press International and Keisaburo Shimamoto, 34, of Newsweek were also killed in the crash.

Ralph Graves, then LIFE magazine's managing editor, remembered the Englishman as 'the single bravest and most dedicated war photographer I know of,' in a moving tribute he wrote following Burrows' death.

'He spent nine years covering the Vietnam War under conditions of incredible danger, not just at odd times but over and over again.'

'The war was his story, and he would see it through. His dream was to stay until he could photograph a Vietnam at peace,' Mr Graves added in the 1971 issue dedicated to the fallen correspondent.

Forging ahead: U.S. Marine Phillip Wilson as he fords a waist-deep river with a rocket launcher over his shoulder during fighting near the DMZ. Five days after this photograph was taken, he was killed in combat

Comrade: American Marines tending to a wounded soldier during a firefight south of the DMZ

Fifty years ago, in March 1965, 3,500 U.S. Marines landed in South Vietnam. They were the first American combat troops on the ground in a conflict that had been building for decades. The communist government of North Vietnam (backed by the Soviet Union and China) was locked in a battle with South Vietnam (supported by the United States) in a Cold War proxy fight. The U.S. had been providing aid and advisors to the South since the 1950s, slowly escalating operations to include bombing runs and ground troops. By 1968, more than 500,000 U.S. troops were in the country, fighting alongside South Vietnamese soldiers as they faced both a conventional army and a guerrilla force in unforgiving terrain. Each side suffered and inflicted huge losses, with the civilian populace suffering horribly. Based on widely varying estimates, between 1.5 and 3.6 million people were killed in the war. This photo essay, part one of a three-part series, looks at the earlier stages of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, as well as the growing protest movement, between the years 1962 and 1967. Tomorrow, a look at the later years as the war wound down. Wounded: U.S. Marines carry the injured during a firefight near the southern edge of the DMZ, Vietnam, October 1966 Worn down: An American Marine during Operation Prairie Bloody: Marines carry an injured soldier back to the medics for treatment following an assault on Hill 484, Vietnam, October 1966 (left). An American soldier (right) with a bandaged head wound looking dazed after participating in Operation Prairie just south of the DMZ An estimated 1,329 Americans were killed during the operation. More than 58,000 Americans lost their lives in the conflict in Indochina that ended in 1975. One of the most famous images in the collection by Burrows is the shot 'Reaching Out,' the moment when wounded Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie, photographed with a blood-stained bandage tied around his head, is drawn to his fellow soldier, who lays wounded on the ground. Though some of the pictures by the renowned war photographer did appear in the magazine in the 1970s, some never made it to publication and are being seen for the first time in the LIFE.com gallery. The war correspondent has been praised for his indefatigable commitment to chronicle the conflict through pictures that communicated the horror of the fighting and honored the lives lost in the conflict in a way words just never could fully transmit. Reaching Out: Wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie (center, with bandaged head) reaches toward a stricken comrade after a fierce firefight Read more: Battle: A dazed, wounded American Marine gets bandaged during Operation Prairie Fallen: Four Marines recover the body of Marine fire team leader Leland Hammond as their company comes under fire near Hill 484. (At right is the French-born photojournalist Catherine Leroy) Burrows himself suffered a tragic end as he worked on the front lines, he was killed on February 10, 1971 over Laos when his helicopter was shot down. He was 44-years-old. Fellow photographers Henri Huet, 43, of the Associated Press, Kent Potter, 23, of United Press International and Keisaburo Shimamoto, 34, of Newsweek were also killed in the crash. Ralph Graves, then LIFE magazine's managing editor, remembered the Englishman as 'the single bravest and most dedicated war photographer I know of,' in a moving tribute he wrote following Burrows' death. 'He spent nine years covering the Vietnam War under conditions of incredible danger, not just at odd times but over and over again.' 'The war was his story, and he would see it through. His dream was to stay until he could photograph a Vietnam at peace,' Mr Graves added in the 1971 issue dedicated to the fallen correspondent. Read more: http://life.time.com/history/vietnam-photo-essay-by-larry-burrows-one-ride-with-yankee-papa-13/#ixzz2J552mX00 Comrade: American Marines tending to a wounded soldier during a firefight south of the DMZ Though the lost photographers were mourned, their remains were not discovered until 37 years later thanks to the tireless effort spearheaded by AP writer Richard Pyle. The remains of Mr Burrows, Mr Buet, Mr Potter and Mr Shimamoto now sit in a stainless-steel box beneath the floor of the Newseum in Washington, D.C., part of a memorial gallery honoring journalists killed in the line of duty. A total of 2,156 individuals, dating back as far as 1837, are included in the museum's memorial.

Wounded: U.S. Marines carry the injured during a firefight near the southern edge of the DMZ, Vietnam, October 1966

Worn down: An American Marine during Operation Prairie

Bloody: Marines carry an injured soldier back to the medics for treatment following an assault on Hill 484, Vietnam, October 1966 (left). An American soldier (right) with a bandaged head wound looking dazed after participating in Operation Prairie just south of the DMZ

|

Prior to the U.S. air strikes, top officials in Washington had reason to doubt that any Aug. 4 attack by North Vietnam had occurred. Cables from the U.S. task force commander in the Tonkin Gulf, Captain John J. Herrick, referred to "freak weather effects," "almost total darkness" and an "overeager sonarman" who "was hearing ship's own propeller beat."

One of the Navy pilots flying overhead that night was squadron commander James Stockdale, who gained fame later as a POW and then Ross Perot's vice presidential candidate. "I had the best seat in the house to watch that event," recalled Stockdale a few years ago, "and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets -- there were no PT boats there.... There was nothing there but black water and American fire power."

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson commented: "For all I know, our Navy was shooting at whales out there."

But Johnson's deceitful speech of Aug. 4, 1964, won accolades from editorial writers. The president, proclaimed the New York Times, "went to the American people last night with the somber facts." The Los Angeles Times urged Americans to "face the fact that the Communists, by their attack on American vessels in international waters, have themselves escalated the hostilities."

An exhaustive new book, The War Within: America's Battle Over Vietnam, begins with a dramatic account of the Tonkin Gulf incidents. In an interview, author Tom Wells told us that American media "described the air strikes that Johnson launched in response as merely `tit for tat' -- when in reality they reflected plans the administration had already drawn up for gradually increasing its overt military pressure against the North."

Why such inaccurate news coverage? Wells points to the media's "almost exclusive reliance on U.S. government officials as sources of information" -- as well as "reluctance to question official pronouncements on `national security issues.'"

Daniel Hallin's classic book The `Uncensored War' observes that journalists had "a great deal of information available which contradicted the official account [of Tonkin Gulf events]; it simply wasn't used. The day before the first incident, Hanoi had protested the attacks on its territory by Laotian aircraft and South Vietnamese gunboats."

What's more, "It was generally known...that `covert' operations against North Vietnam, carried out by South Vietnamese forces with U.S. support and direction, had been going on for some time."

In the absence of independent journalism, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution -- the closest thing there ever was to a declaration of war against North Vietnam -- sailed through Congress on Aug. 7.

One of the Navy pilots flying overhead that night was squadron commander James Stockdale, who gained fame later as a POW and then Ross Perot's vice presidential candidate. "I had the best seat in the house to watch that event," recalled Stockdale a few years ago, "and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets -- there were no PT boats there.... There was nothing there but black water and American fire power."

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson commented: "For all I know, our Navy was shooting at whales out there."

But Johnson's deceitful speech of Aug. 4, 1964, won accolades from editorial writers. The president, proclaimed the New York Times, "went to the American people last night with the somber facts." The Los Angeles Times urged Americans to "face the fact that the Communists, by their attack on American vessels in international waters, have themselves escalated the hostilities."

An exhaustive new book, The War Within: America's Battle Over Vietnam, begins with a dramatic account of the Tonkin Gulf incidents. In an interview, author Tom Wells told us that American media "described the air strikes that Johnson launched in response as merely `tit for tat' -- when in reality they reflected plans the administration had already drawn up for gradually increasing its overt military pressure against the North."

Why such inaccurate news coverage? Wells points to the media's "almost exclusive reliance on U.S. government officials as sources of information" -- as well as "reluctance to question official pronouncements on `national security issues.'"

Daniel Hallin's classic book The `Uncensored War' observes that journalists had "a great deal of information available which contradicted the official account [of Tonkin Gulf events]; it simply wasn't used. The day before the first incident, Hanoi had protested the attacks on its territory by Laotian aircraft and South Vietnamese gunboats."

What's more, "It was generally known...that `covert' operations against North Vietnam, carried out by South Vietnamese forces with U.S. support and direction, had been going on for some time."

In the absence of independent journalism, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution -- the closest thing there ever was to a declaration of war against North Vietnam -- sailed through Congress on Aug. 7.

(Two courageous senators, Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska, provided the only "no" votes.) The resolution authorized the president "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression."

The rest is tragic history.

The rest is tragic history.

With a country in shambles, as a result of the Vietnam War, thousands of young men and women took their stand through rallies, protests, and concerts. A large number of young Americans opposed the war in Vietnam. With the common feeling of anti-war, thousands of youths united as one. This new culture of opposition spread like wild fire with alternate lifestyles blossoming, people coming together and reviving their communal efforts, demonstrated in the Woodstock Art and Music Festival.

"All we are asking is give peace a chance," was chanted throughout protests, and anti-war demonstrations. Timothy Leary's famous phrase, "Tune in, turn on, and drop out!" America's youth was changing rapidly.

Never before had the younger generation been so outspoken. 50,000 flower children and hippies traveled to San Francisco for the "Summer of Love," with the Beatles' hit song, "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band as their light in the dark. The largest anti-war demonstration in history was held when 250,000 people marched from the Capitol to the Washington Monument, once again, showing the unity of youth.Counterculture groups rose to every debatable occasion.

"All we are asking is give peace a chance," was chanted throughout protests, and anti-war demonstrations. Timothy Leary's famous phrase, "Tune in, turn on, and drop out!" America's youth was changing rapidly.

Never before had the younger generation been so outspoken. 50,000 flower children and hippies traveled to San Francisco for the "Summer of Love," with the Beatles' hit song, "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band as their light in the dark. The largest anti-war demonstration in history was held when 250,000 people marched from the Capitol to the Washington Monument, once again, showing the unity of youth.Counterculture groups rose to every debatable occasion.

The Dec 14, 1897 Truce of Biyak-na-Bato temporarily halted the revolution. Gen. Emilio F. Aguinaldo brought Del Pilar to Hong Kong (LEFT, photo taken in Hong Kong in early 1898).

The Dec 14, 1897 Truce of Biyak-na-Bato temporarily halted the revolution. Gen. Emilio F. Aguinaldo brought Del Pilar to Hong Kong (LEFT, photo taken in Hong Kong in early 1898).

and stone barricades, all of which dominated the narrow trail that zigzagged up towards the pass.

and stone barricades, all of which dominated the narrow trail that zigzagged up towards the pass. spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair.

spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair.